Glycation is one of the basic root causes of endogeneous (intrinsic) skin ageing and a very challenging one or almost impossible one to reverse. Glycation is an ageing reaction which begins in early life, developing clinical symptoms at around 30, and progressively accumulates in tissues and skin due to the glycated collagens that are difficult to be decomposed. Glycation occurs naturally in the body when sugars react with proteins and lipids to form advanced glycation end products (AGEs). AGEs can be exogenously ingested (through food consumption), inhaled via tobacco or endogenously produced and formed both intracellularly and extracellularly. AGE modifications lead to dermal stiffening, diminished contractile capacity of dermal fibroblasts, lack of elasticity in the connective tissues, contribute to hyperpigmentation and a yellowish skin appearance. The formation of AGEs is amplified through exogenous factors, e.g., ultraviolet radiation.

AGEs cause changes in the skin through 3 processes:

One study published in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology found that levels of AGEs were higher in the skin of older individuals compared to younger ones. The study also showed that there was a correlation between the level of AGEs and the severity of skin ageing. This suggests that inhibiting the production or accumulation of AGEs in the skin is a potential target for anti-ageing interventions or skin ageing management. AGEs are complex and heterogeneous, more than a dozen AGEs have been detected (however not all) in tissues and can be divided into three categories according to their biochemical properties. AGEs are formed through four pathways:

GLYCATION INHIBITION IS KEY AGEs can be crosslinked through side chains to form a substance of very high molecular weight, which is not easily degraded. The consequences from skin glycation are irreversible. This makes prevention or inhibition of the process the best potential strategy to maintain skin health and ageing skin management. One way to do this is by altering the diet to reduce the intake of sugars and carbohydrates, which are known to contribute to glycation. Several studies have found that reducing sugar intake can result in significant improvements in skin health, including reducing wrinkles and improving skin texture.

AGE inhibitors

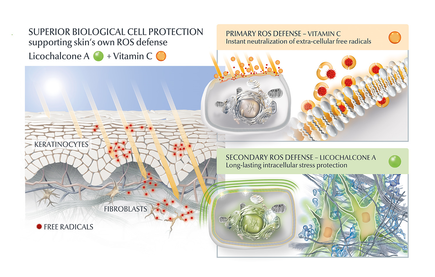

Another potential strategy is the use of topical agents that inhibit the formation or accumulation of AGEs in the skin. One study published in the Journal of Cosmetic Science found that a cream containing carnosine, a peptide that inhibits glycation, improved skin elasticity and reduced the appearance of wrinkles in individuals with ageing skin. Skincare containing NAHP or Acetyl Hydroxyproline inhibits the formation of AGEs significantly (in vitro), most likely through a mechanism where NAHP competes with the proteins for the sugar. Finally, NAHP sacrifices itself in place of the proteins and gets (at least partially) glycated. NAHP also prevents loss of cellular contractile forces in a glycated in vitro dermis model and counteracts the diminished cell-matrix interaction that is caused by glyoxal-induced AGE formation. Anti-Oxidants Moreover, I would suggest to combine those ingredients with an ingredient like Licochalcone A. Numerous high ranked publications support that Licochalcone A protects cells from oxidative stress mediated by e.g. UV and HEVIS (blue light) induced reactive oxidative species (ROS). Due to the activation and nuclear translocation of the transcription factor NrF2, the expression of anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and detoxifying enzymes are induced. These enzymes protect the skin cells (like keratinocytes and fibroblasts) from ROS-induced damage, like lipid peroxidation and DNA as well as protein damage. If Licochalcone A is combined with L-Ascorbic Acid, (the most active form of Vitamin C), it supporting skin's own collagen production, provides superior biological cell protection amongst other relevant benefits. My absolute favourite product is Eucerin Hyaluron-Filler Vitamin C Booster which I use daily as a serum in my morning routine. GLYCATION AND SKIN HEALTH Acne In addition to its role in ageing, glycation in the skin has also been linked to a range of skin health problems. One study published in the Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology found that the level of AGEs in the skin was significantly higher in individuals with acne than in those without acne. The study also showed that treating acne with a topical antibiotic significantly reduced the levels of AGEs in the skin. Atopic Dermatitis Another study published in the Journal of Investigative Dermatology found that individuals with atopic dermatitis had higher levels of AGEs in their skin than healthy individuals. This suggests that glycation may play a role in the development of inflammatory skin conditions. Diabetes + Woundhealing The correlation between high sugar levels and skin ageing can be seen in diabetic patients, where one-third of this population has skin complications. A prominent feature of ageing human skin is the fragmentation of collagen fibers, which severely damages the structural integrity and mechanical properties of the skin. Elevated levels of MMP-1 and MMP-2 and higher crosslinked collagen in the dermis of diabetic skin lead to the accumulation of fragmented and crosslinked collagen, thereby impairing the structural integrity and mechanical properties of dermal collagen in diabetes. Collagen crosslinking makes it impossible for them to easily repair, resulting in reduced skin elasticity and wrinkles. Keratinocytes and fibroblasts are the main cells involved in wound healing, but due to the high glucose (HG) microenvironment in diabetics, the functional state of these cells is impaired, thereby accelerating cellular senescence (programmed cell death). Conclusion We can't completely stop the glycation process, therefore it's important that we inhibit it from a young age onwards, hence monitor the sugar intake of our children, use daily SPF and invest in good dermo-cosmetic products containing ingredients like NAHP and powerful anti-oxidants like L-Ascorbid Acid (Vitamin C is needed for the production of collagen) and Licochalcone A (also anti-inflammatory). Preventing signs of ageing, specifically caused by glycation is most effective. If your skin shows (advanced) signs of ageing, you can get visible improvement using skin component (hyaluron, collagen and elastin) bio-stimulating ingredients like Retinol, Bakuchiol, Arctiin, Creatine or Glycine Saponin. Consult your dermatologist if you wish to improve your skin's appearance or skin health issues. Take care Special thanks: Ph.D. dr Julia M. Weise Manager Biological Testing & Dorothea Schweiger Lab Manager Facial Skin Biology Beiersdorf HQ Hamburg

Comments

12/15/2018 Comments Aquatic wrinkles

After about spending some time in bathtub or in the pool, we can notice that our skin on particularly finger tops and toes start to wrinkle up. This wrinkling effect is believed to have a function.

When wet, things tend to be more slippery and our sophisticated skin is designed to counteract this by wrinkling up in a pattern optimised to provide a drainage network that improves grip, much like the tires on a car according to a study. Link to original publication. However, other studies would contradict that there would be a functional benefit for so called aquatic wrinkles. The osmosis theory Water molecules moving trough a semipermeable membrane from a low concentration area to a high concentration area is a process called osmosis. The shrinking and expanding effects of osmosis takes place simultaneously outer layer of the skin, causing wrinkles. The skin's outermost layer is also known as stratum corner could be responsible for this wrinkly reaction, The top layer of our skin consists of dead corneocytes. The longer these cells are attached to the skin, the bigger they are. The size of the corneocytes we actually use to objectively measure the skin's renewal and desquamation (shedding of cells) process. These dead (keratin containing) skin cells may absorb water and swell. The lower layer with living cells doesn't swell up. As top layer (which is increased in size) is still attached to the layer beneath, a wrinkly pattern is formed. The layer of dead skin cells is thicker at the palms of our hands and soles of our feet, the wrinkling effect is more evident. This response occurs more quickly in freshwater than seawater. Moreover, when we are exposed to water for a longer time, the water-repelling film on top of the outer layer of the skin may get impaired. The sympathetic nervous system / microcirculation theory It's known that there is a relationship between the wrinkling-effect and blood vessels constricting (narrowing) below the skin. When hands and feet are soaked in water, the nerve fibres in the skin shrink and the body temperature regulators loses volume. Therewith the top layer of the skin is pulled downward and the wrinkling pattern is formed. It is proven that wrinkling-effect response is impaired, if the nerves and/or blood vessels are damaged. Therewith the wrinkling effect can even be used to determine proper functioning of the sympathetic nervous system and/or skin's microcirculation. There is evidence that the wrinkling effect is impaired in patients suffering from diabetes: link to article. Regardless the cause, aquatic wrinkles disappear fast and the skin returns to normal once the water has evaporated. Take care. |

CategoriesAll Acne Ageing Aquatic Wrinkles Armpits Biostimulators Blue Light & HEVIS Cleansing CoQ10 Cosmetic Intolerance Syndrome Deodorant Dermaplaning Diabetes Dry Skin Evidence Based Skin Care Exfoliation Exosomes Eyes Face Or Feet? Facial Oils Fibroblast Fingertip Units Gendered Ageism Glycation Gua Sha Hair Removal Healthy Skin Heat Shock Proteins Hormesis Humidity Hyaluron Hyaluronidase Hypo-allergenic Indulging Jade Roller Licochalcone A Luxury Skin Care Lymphatic Vessel Ageing Malar Oedema Menopause Mitochondrial Dysfunction Mood Boosting Skin Care Neurocosmetics Ox Inflammageing PH Balance Skin Photo Biomodulation Polynucleotides Psoriasis Regenerative Treatments Review Safety Scarring Sensitive Skin Skin Care Regimen Skin Flooding Skin Hydration Skin Senescence Skip-Care Sleep Slugging Sunscreen Tanning Under Eye Bags Vitamin C Well Ageing Skin Care Wound Healing Wrinkles

Archives

April 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed